Have questions about voting or issues voting on Election Day?

Call 866-OUR-VOTE

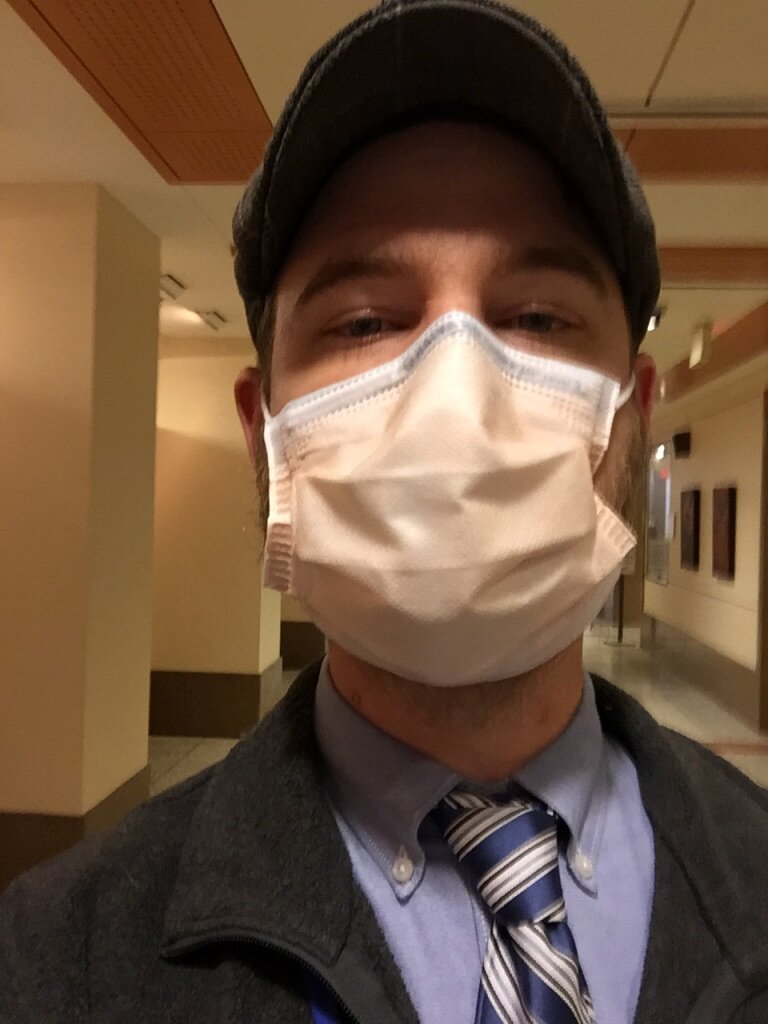

Millions of people in the United States, myself included, have medical conditions that have been deemed “pre-existing” by insurance companies.

Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, it was entirely legal to deny insurance coverage to those of us with pre-existing conditions.

Since the passage of the ACA, there has been a decade of attempts to overturn it, led primarily by Congressional Republicans and more recently by the current administration, without any real attempt to create an alternative that could protect those of us with pre-existing conditions.

At the same time, it’s become very clear that protecting coverage for pre-existing conditions has become very popular, which has led to the bizarre reality of a certain group of political figures claiming that they care deeply about protecting pre-existing conditions coverage while pursuing policies that do exactly the opposite.

I saw this on full display in the Senate debate here in North Carolina, where incumbent Senator Thom Tillis waxed eloquent about healthcare after building a political career on denying the expansion of Medicaid and attacking the ACA. NBC recently ran an article about the way other Republican Senators are falsifying or misrepresenting their positions on pre-existing conditions on the campaign trail. The President was challenged on this very topic by both a voter and the moderator at an ABC News Town Hall. He’s sought to obscure the issue by issuing an executive order about pre-existing conditions, but the order basically recommends that someone, anyone, figure out the issue (which, to be clear, hasn’t been figured out in a decade of attacks on the ACA) and of course does not have the force of a law.

Words — in a book or in an executive order — don’t protect pre-existing conditions. Laws do.

But here’s the thing: Words don’t protect pre-existing conditions. Laws do.

Obfuscating words on a campaign trail don’t do it. Vague words in an executive order don’t do it. Interrupting words spoken over voter concerns at a town hall don’t do it. Passionate words in my book about the topic don’t do it. Laws do.

Meanwhile, Senate Republicans just voted to confirm Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, with no Democrats voting in favor, in a rushed process that took place while millions of Americans have already voted. One of the first cases she will hear will be a case to overturn the ACA and its protection of pre-existing conditions, a case that the current administration has been fully supportive of. As NPR reports, if the Court overturns the ACA, “protecting preexisting conditions could be harder than it sounds.”

In Grace is a Pre-Existing Condition, I wrote this:

“When I hear reports about threats to these protections, the fear and anxiety I felt when I first tread that letter from the insurance company come rushing back. It makes me scared. And it makes me angry.”

That fear and anger, the tightness in my chest I’ve carried around with me for years, is back in full force right now.

And I’ll be honest: words won’t soothe that anxiety.

Laws will.

———